Steve Denning has been writing a new book, The Leaders Guide to Radical Management, which is due out in November 2010. It's an interesting take on the idea that traditional management no longer works in today's economy. The (traditional) inward focus on "what we do" forces companies down a path of command and control. Seeing various discussions of Radical Management around the web, the general idea is to focus on the customers. What will delight them? What will make them talk about you (positively) to their colleagues and customers?

Steve Denning has been writing a new book, The Leaders Guide to Radical Management, which is due out in November 2010. It's an interesting take on the idea that traditional management no longer works in today's economy. The (traditional) inward focus on "what we do" forces companies down a path of command and control. Seeing various discussions of Radical Management around the web, the general idea is to focus on the customers. What will delight them? What will make them talk about you (positively) to their colleagues and customers?

This leads me to one of his recent posts at his blog, Why Do Great KM Programs Fail?. It is very much connected to the ideas of his book. It also connects to things I have observed as well. This is how he sets up the lengthy discussion:

[I was] somewhat surprised when I found that most of the great knowledge management programs that I observed in organizations were eventually closed down, sidelined or shifted to the periphery. The managements of these organizations didn’t seem to appreciate great KM accomplishments right in front of their noses.

As he says, it doesn't just happen in KM. It happens in many programs. But the key finding is that the failure happens when the underlying philosophy of the program works against the way the business is run. It maybe glib to say that knowledge management requires a culture of openness and trust, but when the overarching business is run on a hierarchical, need-to-know basis and distrust, big KM isn't going to get very far. Look at the discussion of culture when people are talking about Enterprise 2.0. The same thing happens with Lean implementations in the United States - just look at the common acronymization: less employees are needed. I hate to say that this happens in Theory of Constraints implementations too. They get so far, and then either stall out or vanish completely because the emphasis on throughput and growing are at odds with the much more common philosophy of cost containment. And the implementations are often at a local level, rather than global which would provide more staying power.

What is the solution? How do you keep these great and valuable programs from falling off as soon as the program sponsor moves to a different role? Denning offers some specifics for KM programs. But in general, you either develop a management structure that works for the long haul, or you prepare for the inevitable dismantling of your program. Denning argues for more openness and self-organizing teams with a focus on the customer. Stop focusing on cost and "the way we've always done things" because those don't get you growth.

Several others have commented on this post too: Nick Milton gives some great stories from his experience and wraps up with sage advice: don't think one success will spell victory. You need to let your creation flower and blossom in ways that you never expected. Nimmy links and pulls some key extracts from Steve's post. Chris Janney has a dense post on the topic, somewhat in agreement and somewhat critical of Denning. Strangely: I could not find any other references to Steve's article, even with using the Google "link" structure for search, even though it seems that it should have generated more commentary.

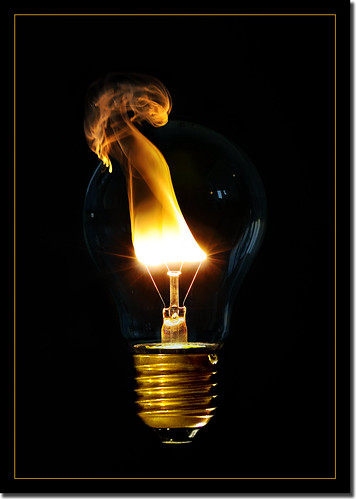

[Photo: "failure" by Beat Kueng]